Making WavesIn a seminar co-organized by Stanford University and the American Institute of Mathematics, Soundararajan announced that he and Roman Holowinsky have proven a significant version of the quantum unique ergodicity (QUE) conjecture. "This is one of the best theorems of the year," said Peter Sarnak, a mathematician from Princeton who along with Zeev Rudnick from the University of Tel Aviv formulated the conjecture fifteen years ago in an effort to understand the connections between classical and quantum physics. "I was aware that Soundararajan and Holowinsky were both attacking QUE using different techniques and was astounded to find that their methods miraculously combined to completely solve the problem," said Sarnak. Both approaches come from number theory, an area of pure mathematics which recently has been found to have surprising connections to physics.The motivation behind the problem is to understand how waves are influenced by the geometry of their enclosure. Imagine sound waves in a concert hall. In a well-designed concert hall you can hear every note from every seat. The sound waves spread out uniformly and evenly. At the opposite extreme are "whispering galleries" where sound concentrates in a small area.

|

|

Quantum chaosThe quantum unique ergodicity conjecture (QUE) comes from the area of physics known as "quantum chaos." The goal of quantum chaos is to understand the relationship between classical physics--the rules that govern the motion of macroscopic objects like people and planets when their motion is chaotic, with quantum physics--the rules that govern the microscopic world."The work of Holowinsky and Soundararajan is brilliant," said physicist Jens Marklof of Bristol University, "and tells us about the behaviour of a particle trapped on the modular surface in a strong magnetic field."

In their QUE conjecture, Rudnick and Sarnak hypothesized that for a large class of systems, unlike the stadium there are no scars or bouncing ball states and in fact all states become evenly distributed. Holowinsky and Soundararajan's work shows that the conjecture is true in the number theoretic setting. |

|

Highly excited statesThe conjecture of Rudnick and Sarnak deals with certain kinds of shapes called manifolds, or more technically, manifolds of negative curvature, some of which come from problems in higher arithmetic. The corresponding waves are analogous to highly excited states in quantum mechanics.Soundararajan and Holowinsky each developed new techniques to solve a particular case of QUE. The "waves" in this setting are known as holomorphic Hecke eigenforms. The approaches of both researchers work individually most of the time and miraculously when combined they completely solve the problem. "Their work is a lovely blend of the ideas of physics and abstract mathematics," said Brian Conrey, Director of the American Institute of Mathematics. According to Lev Kaplan, a physicist at Tulane University, "This is a good example of mathematical work inspired by an interesting physical problem, and it has relevance to our understanding of quantum behavior in classically chaotic dynamical systems."

|

|

Soundararajan, Stanford University

|

Roman Holowinsky,

|

|

Please address questions or comments to questions(at)aimath.org AIM receives major funding from Fry's Electronics and the NSF. |

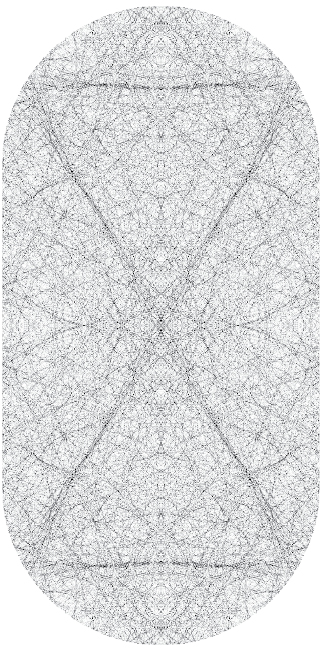

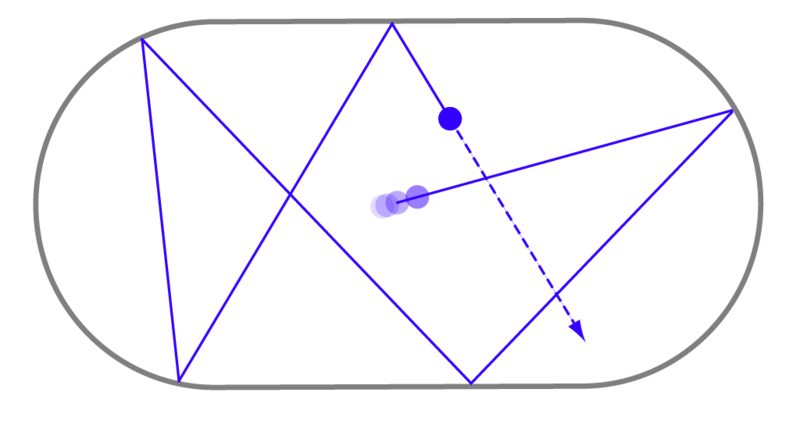

The problems of quantum chaos can be understood in terms of billiards.

On a standard rectangular billiard table the motion of the

balls is predictable and easy to describe. Things get more interesting

if the table has curved edges, known as a "stadium." Then it turns out most paths are chaotic and

over time fill out the billiard table, a result proven by the mathematical

physicist Leonid Bunimovich.

The problems of quantum chaos can be understood in terms of billiards.

On a standard rectangular billiard table the motion of the

balls is predictable and easy to describe. Things get more interesting

if the table has curved edges, known as a "stadium." Then it turns out most paths are chaotic and

over time fill out the billiard table, a result proven by the mathematical

physicist Leonid Bunimovich.